We asked Lorin Nielsen, Head Horticulturist at Epic Gardening and Botanical Interests, to shed some light on some of our seed choices when it comes to store bought seeds and those collected at home.

Open-pollinated

An open-pollinated seed is pollinated via natural means, such as wind, bees, etc. These seeds produce "true-to-type" plants that mimic the growth habit of their parent plant - so, for instance, if you saved seeds from a 'California Wonder' bell pepper, you could plant those seeds and grow more 'California Wonder' peppers. There is more on the topic of open-pollinated seeds below where we talk about home gardeners saving their own seeds.

Hybrid

Most commercially available seeds began as a hybrid - an intentional cross-pollination by humans to create a new cultivated variety of a particular plant species. Humans have intentionally crossed varieties for centuries to create varieties with improved flavor, color, shape, or disease resistance. Some hybrids produce viable seeds, and some don't, with some even bred to be nearly seedless. Those that are viable and do grow may not grow "true-to-type," meaning they may not produce the same type of plant as their parent plant did.

However, if a hybrid produces viable seeds and grows true-to-type, plant breeders can continue to grow them out to stabilize the variety. This process reinforces the cross-pollination and genetics of this new variety. After years, if they continue to produce that same type of produce, they're considered a stabilized hybrid. A good example of this is the 'Yolo Wonder' pepper, an intentional hybrid between the 'California Wonder' and 'Elephant Trunk' pepper varieties. After it was stabilized, the seeds from each 'Yolo Wonder' plant produced true-to-type, and people could grow that variety year after year; it's now an open-pollinated seed.

Heirloom

"Heirloom" is the most confusing term because it's not standardized in the seed industry. At Botanical Interests, we consider an heirloom variety to be an open-pollinated and stable variety that produces true-to-type seeds and has been commercially available for over 50 years. Using the two peppers I've mentioned, both 'California Wonder' and 'Yolo Wonder' are considered heirlooms; 'California Wonder' was first introduced in 1928, and 'Yolo Wonder' was first introduced in 1952. Both have been stable for over 50 years and are fan-favorite, reliable bell peppers that continue to be sold today, so we'd consider both heirloom varieties. But if someone took one of those two peppers and bred it with, say, a jalapeno over the years, they might produce a new hybrid variety, and the cycle would start anew with that one.

However, "heirloom" does not always mean the variety is over 50; if every other seed company considers a seed an "heirloom" variety, we will follow their lead. An excellent example is the 'Cherokee Purple' tomato, which was stabilized in the 1990s; it's not quite 50 years old, but the industry considers it an heirloom variety. It would confuse our customers if our Cherokee Purple tomato wasn't considered an heirloom, but everyone else's was!

GMO and the Safe Seed Pledge

GMO stands for "genetically modified organism." These bioengineered varieties can include genetic material from entirely different species of plants. A good example is Norfolk's Purple Tomato, released last year. The world's first bioengineered tomato was developed using two genes from snapdragons to increase the tomato's anthocyanin content, turning the fruit a vivid purple. Genetic modification like this is becoming more common; other examples are the pink-fleshed pineapples that became so popular a few years back or the petunia that included genetics from bioluminescent mushrooms, so it glows faintly in the dark.

Many people are concerned about the safety of genetically modified produce and prefer to avoid them. Years back, many companies (Botanical Interests among them) signed the "Safe Seed Pledge", a promise that the company would avoid genetically modified seeds. We took this a step further and have had our seeds tested by the Non-GMO Project, the first American testing process to confirm that seeds have not intentionally or unintentionally become contaminated by GMO material. We're proud to say our seeds are Non-GMO Project Verified and that we test our seeds regularly with the project to ensure we stay GMO-free.

Treated and Untreated.

Seeds can be treated in many different ways. For instance, commercial lawn grass seed is often treated with a coating that absorbs water and keeps it moist until it germinates. Some seeds can be treated with bacterial inoculants, such as Rhizobium, to help a leguminous plant fix nitrogen in its root system. Seeds can be treated with antifungal agents or pest prevention aids, etcetera. There are a lot of different treatment methods out there, each with a specific purpose.

In contrast, an "untreated" seed is precisely as it grew and was harvested, free from additives. Botanical Interests carries only untreated seeds. While there are some great seed treatments out there, we prefer to leave the choice of seed treatment up to each individual gardener, as they know what they want to use in their garden! The closest thing we have to treatment is an inert clay coating on some tiny seeds to make picking up just one seed easier.

Saving Seeds at Home

Home gardens are usually open-pollinated environments so cross-pollination can happen. This doesn't mean you shouldn't save seeds from open-pollinated plants; you absolutely should! But to reinforce the genetics of your favorite variety it doesn't hurt to work in some "new" (store bought) seeds every few years. Grow some of your favorite variety of squash side-by-side from both homegrown seeds and some brand-new store-bought seeds of the same variety, and intentionally cross-pollinate the two to reinforce the original genetics you loved from that variety in the seeds you harvest that year.

If you are growing multiple varieties of a plant, for instance, if you grow 4 tomato varieties, you may have accidental cross-pollination. If you only grow one variety, you can be relatively confident it will not cross-pollinate with another variety as long as nobody nearby is growing tomatoes.

In a farm setting with an entire field of plants of the same species and variety, the outermost plants would be more susceptible to cross-pollination if your farm were bordered by someone growing a different variety of the same species. Those towards the center of the field are far more likely to be pollinated by the same variety of their species. For example, a cornfield would reliably have the correct variety throughout its center. Still, the outermost row or two of corn might cross-pollinate if a neighboring farm is also growing corn. To prevent this, many farmers either leave large gaps between their primary fields and neighboring fields or place windbreak plants to prevent wind transfer of pollen from external fields into their fields (as corn pollen readily travels in the wind).

When we're talking specifically about seed production, more stringent measures are usually in place. Seed farmers only want the correct species and variety to ensure the continuity of their varietal strain, so they usually provide a gap of up to a mile between their plants and any other plants of the same species. This prevents accidental cross-pollination

Let's talk about a plant known to have come from accidental cross-pollination: the Lakota squash. This popular winter squash variety has a fascinating history.

In the 1820s, soldiers at Nebraska's Fort Robinson were given squash seeds by an unnamed tribe. After growing them at the fort for a few years, a civilian employee at the fort shared some seeds with his sister, Martha Newman, who started to grow the tribal squash. Originally, it was described as a long, cylindrical squash streaked with orange and green. She faithfully saved seeds from her squash each year, and when she moved away from the area she brought her saved seeds with her.

But she didn't grow just the fort's squash variety; Martha also grew Hubbard squash. Years of cross-pollination from local pollinators started hybridizing the Hubbard squash with the native squash variety. The shape of the resulting fruit gradually changed; while it kept its green and orange streaks, it started to produce teardrop-shaped fruit like Hubbard squash. Mrs. Newman also shared her seeds with other people, including a friend, Alice Graham. Eventually, Ms. Graham shared seeds with D.P. Coyne, a University of Nebraska breeder; he stabilized the variety and named it "Lakota" after a well-known Plains tribal group, and eventually, they became commercially available.

This same process can happen in your home garden if two varieties of the same species are grown side by side for multiple years, but accidental hybridization through cross-pollination is slow. You won't see immediate changes from year to year, but over a few years, you might see subtle shifts; perhaps the fruit will be a little smaller or larger, the shape will gradually become a bit different, or the color will change.

If you want to save seeds but don't want to risk accidental cross-pollination, it's best to stick to growing only one variety per species. For squash, raising only one Cucurbita maxima variety or only one Cucurbita pepo variety will prevent your plants from cross-breeding via your local pollinators, the wind, or even accidental pollen on your hands. Unfortunately, most of us like to grow multiple varieties (I know I can't pick just one tomato!), so we should expect some genetic drift in our saved seeds over the years.

Botanical Interests and Epic Gardening

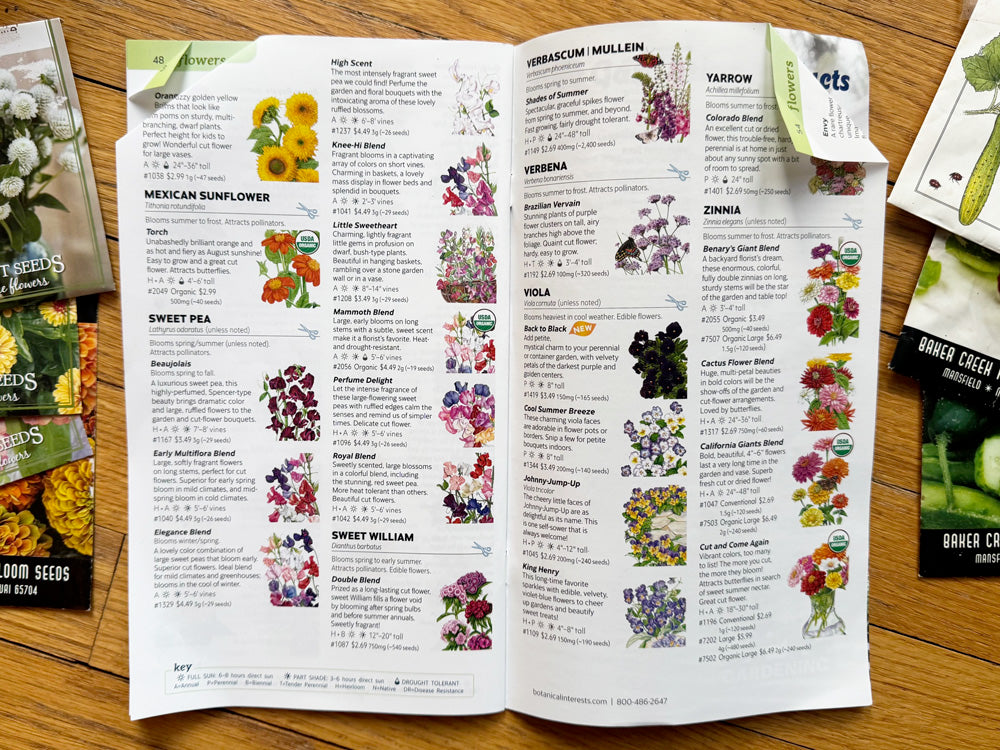

Thirty years ago, in a garage, Botanical Interests got its start. The company's founders, Judy and Curtis, raised their children while simultaneously growing a family seed business devoted to providing high-quality, non-GMO seeds with a large selection of organic or heirloom varieties. While we carry both conventional seeds and hybrids, we pride ourselves on our selection of reliable, tried-and-true organic and heirloom varieties! Our seed packets feature illustrations by botanical artists, and each seed packet is jammed full inside and out with useful information on how to grow the seeds it holds. Botanical Interests seeds can be found online at our website or through our network of small garden centers, markets, and family businesses nationwide.

When the founders decided to retire, they looked for someone who wouldn't just assimilate their company and make it vanish into a larger company. While they had offers from many larger corporations, they chose Epic Gardening to keep their business alive and thriving. This gardening education company has provided free information for almost a decade on how to grow all sorts of plants through thousands of online articles, multiple YouTube channels, a podcast, and more. Still a small business, our devoted team strives to continue the dream of Botanical Interests' original founders.

The old Botanical Interests motto was to "inspire and educate the gardener within," which blended seamlessly with Epic Gardening's motto of "teach the world to grow." Last year, we shifted our company's motto to "We exist to help you grow," and we continue to provide a neverending supply of gardening education (for free!), the tried-and-true seeds we love so much, and a line of gardening equipment that's tested and approved by our team of avid gardeners. We love to help inspire our customers, both new and old, experienced and just learning.

We are proud to be Non-GMO Project Verified. All our seeds are untreated, and our non-hybrid seeds are open-pollinated. Our organic seeds are USDA-certified, and we regularly test each seed lot we carry to ensure they meet or exceed federal germination standards - usually greatly exceeding the national average. And finally, our team is primarily made up of gardeners who genuinely want to share the joy of gardening with the rest of the world, one seed at a time.

Find similar articles:

Plant Ideas & Info Presenting "The Curious Gardener" seed starting Spring Projects